The American commitment to European security has been one of the few constants since World War II. Fractures have started to appear in the alliance, however. In May 2017, German Chancellor Angela Merkel observed that “the times in which we can fully count on others are somewhat over … we Europeans must really take our destiny into our own hands.” At the European Union foreign ministers’ meeting in November, 23 member states agreed to work more closely together on defense.

The American commitment to European security has been one of the few constants since World War II. Fractures have started to appear in the alliance, however. In May 2017, German Chancellor Angela Merkel observed that “the times in which we can fully count on others are somewhat over … we Europeans must really take our destiny into our own hands.” At the European Union foreign ministers’ meeting in November, 23 member states agreed to work more closely together on defense.

For the first time since 1945, Europe faces the possibility of having to maintain its security without American help. Simultaneously, Russia’s current activities—such as its intervention in Georgia, annexation of Crimea, and war against Ukraine—pose the most severe threat to European security since the end of the Cold War.

Even if the United States removes its nuclear weapons from Europe, European leaders most likely will not allow European nuclear deterrence to end. They will be prepared to maintain a credible nuclear deterrent, with or without the United States. Call it the “Eurodeterrent.”

Drastic drawdown

The United States and Western European countries initially established NATO as a military alliance against the Soviet Union. With the end of the Cold War, the threat that gave the organization its purpose dwindled. This allowed European NATO members to cut their military spending, France and Germany to suspend conscription, and France and the United Kingdom to reduce their respective nuclear stockpiles. The United States has removed all but an estimated 150 of its more than 7,000 nuclear weapons that were stationed in several European countries during the Cold War

This drastic disarmament reflects the nature of the security situation in Europe for most of the post-Cold War era: European security has been taken for granted by both the Americans and the Europeans. However, the times of a Europe free of threats seem to be over.

The Putin push

Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has called the collapse of the Soviet Union “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century,” now takes any measure available to him to reverse the European order created after 1989. He perceives the extension of Western values and security through the European Union and NATO as a direct threat to Russia’s position on the continent. Putin seeks to destabilize the European community through propaganda and the financial support of illiberal, anti-European, and pro-Russian parties

In Eastern Europe, he is also increasingly comfortable with using force to achieve his goals, such as preventing Ukraine from developing closer ties with the European Union.

Putin will not be satisfied anytime soon. He “is intent on showing the world [that] Russia is a great power and that he respects strength and takes advantage of perceived weakness. He pushes forward until there is pushback,” writes Robert A. Manning, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

At a July 2017 forum on Capitol Hill, Brad Roberts, director of the Center for Global Security Research at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, explained how Putin’s “theory of victory” against the United States and its allies is built on his perception of Western weakness and hesitation. In 2014, Putin was convinced that the West would let him get away with annexing Crimea and practically invading eastern Ukraine, and he remains convinced that he will not encounter any significant pushback in the future. This belief is rooted in Putin’s view of what Roberts calls the “asymmetry of stake”: Because the Russians have more at stake, Russian threats look more credible than American threats. While Putin is fighting for Russia’s position in the world and, more importantly, his position as the legitimate leader of Russia, all that is at stake for the West is the preservation of liberal values. While the Americans might be willing to defend freedom and democracy with sanctions, they will not resort to bullets and bombs.

In Putin’s mind, the Russian nuclear arsenal ensures that the West stays out of his affairs. According to Alexey Arbatov, a Russian expert on international security and arms control, Putin is largely ignoring the nuclear lessons of the Cold War, and views arms control more critically than the Soviet leadership did. While Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev agreed with US President Ronald Reagan that “nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” Putin does not voice similar reservations. In Arbatov’s formulation, as Roberts described it at last year’s forum, Putin and a small cadre of fellow Russian elites are ready to use the Western fear of a nuclear confrontation to their benefit. Putin is absolutely confident that, should things get serious, the Americans would back down first.

The Trump pull

At the same time that Europeans are facing an increased threat from Russia, it looks as though their oldest friend might abandon them. Although the United States has pulled back most of its nuclear weapons from Europe, it still has about 150 B-61 bombs stationed in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey. This nuclear-sharing program is a powerful deterrent, because the host countries, although they are not considered to be nuclear weapon states under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, would become de facto nuclear weapon states in the event of war. Once the B-61 bombs are loaded on their planes, and American soldiers have entered the Permissive Action Link code, the host countries can select a target and deliver the bombs themselves. A would-be attacker would face seven NATO countries capable of defending Europe with nuclear weapons.

At the same time that Europeans are facing an increased threat from Russia, it looks as though their oldest friend might abandon them. Although the United States has pulled back most of its nuclear weapons from Europe, it still has about 150 B-61 bombs stationed in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey. This nuclear-sharing program is a powerful deterrent, because the host countries, although they are not considered to be nuclear weapon states under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, would become de facto nuclear weapon states in the event of war. Once the B-61 bombs are loaded on their planes, and American soldiers have entered the Permissive Action Link code, the host countries can select a target and deliver the bombs themselves. A would-be attacker would face seven NATO countries capable of defending Europe with nuclear weapons.

Since Donald Trump became US president, the future of this system has become less certain. He has called NATO “obsolete,” refused to mention the treaty’s crucial mutual-aid clause when he addressed the other NATO leaders for the first time (he only did so more than two weeks later), and visibly enjoys his time with Putin much more than his meetings with Merkel or French President Emmanuel Macron.

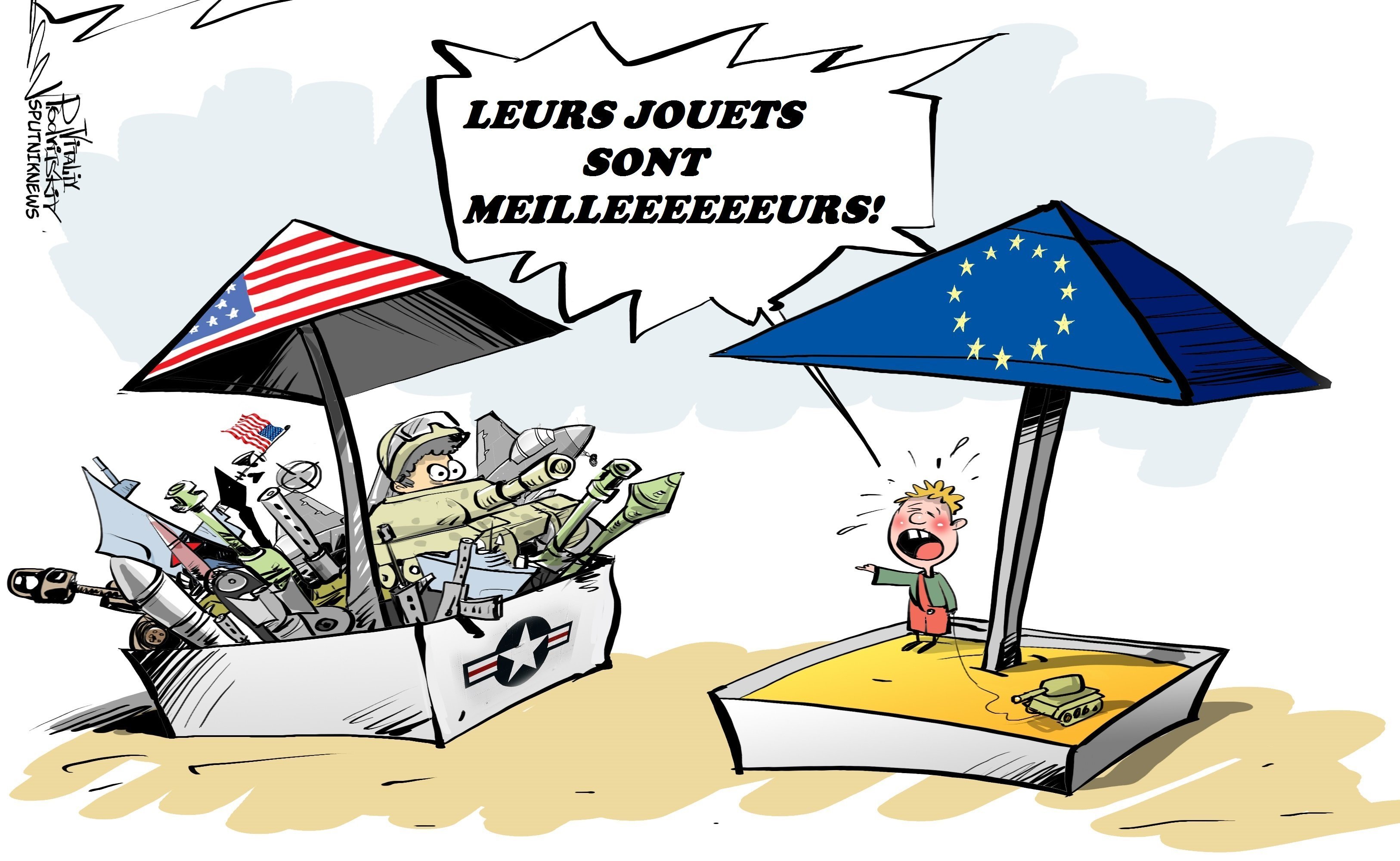

There are no concrete indicators that the United States will leave NATO; Trump has actually increased the number of US troops in Europe. Nevertheless, Trump’s decisions to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Paris Climate Agreement alarmed European leaders, who are increasing their defense budgets. Even if Trump’s opposition to multilateralism does not culminate in a withdrawal from NATO, it is a signal to Putin that the North Atlantic alliance is crumbling, and another factor that validates his perception of the weak West. In this environment, Merkel’s pledge for a Europe that can look after itself does not come as a surprise.

Options for deterrence

What would happen to European deterrence if Europe decided that its security should no longer be imported from across the pond, or if Americans ceased to guarantee the security of their European allies—and removed their nuclear weapons from the continent? Europeans would have to choose one of three options.

What would happen to European deterrence if Europe decided that its security should no longer be imported from across the pond, or if Americans ceased to guarantee the security of their European allies—and removed their nuclear weapons from the continent? Europeans would have to choose one of three options.

The first option would be to rely on the deterrence that would remain after the United States had left, namely the French and British nuclear weapons stationed in those countries. For some of the countries now under the US nuclear umbrella, particularly Germany, this arrangement would not be acceptable.

In Germany, some voices have already called for the second option: a German nuclear program. Berthold Kohler, editor of the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and the political scientist Maximilian Terhalle have both pushed the discussion in this direction. In reality, a nuclear Germany is more than unlikely. A majority of Germans are opposed to a German nuclear program, and no leading German politician, least of all Chancellor Merkel, is currently advocating for German nukes. Such a drastic violation of both the Two Plus Four Treaty (which enabled Germany’s reunification) and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) would give many other nations a pretext under which they could develop their own nuclear weapons, leading to widespread proliferation.

The third option, the so-called “Eurodeterrent,” is a compromise between the two more extreme scenarios. Advocates of the Eurodeterrent, such as the German politician Roderich Kiesewetter, propose that French and perhaps British nuclear weapons should replace the American bombs currently stationed in Europe. The new system would either function similarly to the existing nuclear-sharing program, or a new European military organization would be established to oversee the weapons. In either case, the Eurodeterrent is thought to rely mainly on French weapons and German funding. All this could supposedly be done without proliferation, since the current nuclear arsenals of France and the UK “would likely be sufficient for defending Germany,” according to Jan Techau at the American Academy in Berlin. Although the European arsenal would be dwarfed by Russia in numbers, France possesses the second-strike capability that is crucial for deterrence.

Not just a thought experiment

Several factors explain why a Eurodeterrent is attractive to some experts. By moving some French weapons to Germany and other European countries, the flexibility of the nuclear-sharing program would be preserved. Germany would not lose its status as a de facto nuclear weapon state in case of war, and a potential enemy would have to face several states that could independently deliver nuclear weapons, rather than just France and the United Kingdom. For France, Eurodeterrence would provide an opportunity to become a leader in European security. For the rest of Europe, it would offer independence from the Americans. Furthermore, a homegrown nuclear deterrent is more credible than an imported one. There are some indicators that the Eurodeterrent is not just a thought experiment anymore. In addition to the “public debate” , that was encouraged by European officials, the German Parliament has looked into the legality of such a program. The review, requested by Kiesewetter, reported that German financial support for the stationing of French nuclear weapons on German territory would indeed be legal. The timing of the review might be telling as well—it concluded merely two weeks after the election of Macron, a fierce supporter of close security cooperation between France and Germany.

Several factors explain why a Eurodeterrent is attractive to some experts. By moving some French weapons to Germany and other European countries, the flexibility of the nuclear-sharing program would be preserved. Germany would not lose its status as a de facto nuclear weapon state in case of war, and a potential enemy would have to face several states that could independently deliver nuclear weapons, rather than just France and the United Kingdom. For France, Eurodeterrence would provide an opportunity to become a leader in European security. For the rest of Europe, it would offer independence from the Americans. Furthermore, a homegrown nuclear deterrent is more credible than an imported one. There are some indicators that the Eurodeterrent is not just a thought experiment anymore. In addition to the “public debate” , that was encouraged by European officials, the German Parliament has looked into the legality of such a program. The review, requested by Kiesewetter, reported that German financial support for the stationing of French nuclear weapons on German territory would indeed be legal. The timing of the review might be telling as well—it concluded merely two weeks after the election of Macron, a fierce supporter of close security cooperation between France and Germany.

The Russian threat, American volatility, and European preparations do not necessarily mean that the days of NATO are over. In the current political climate, situations can change quickly, and the next US president might fully commit to his allies. However, European leaders have to plan for the worst. They have to be prepared to deal with possible further fractures, or even an end of the alliance; they have to be prepared for an even more belligerent Russia. Anything else would be naïve.

Felix Wimmer (*) , January, 8th, 2018

(*) Originally from Munich, Felix Wimmer is a senior at Middlebury College in Vermont, majoring in International Politics and Economics. He spent the previous academic year at the University of Oxford...