The U.S. Armed Forces response isn’t to immediately cut its carbon emissions in order to curb climate change. Rather it is to determine how best to defend against the instability and chaos that climate change may bring to the international community, as well as the threat it poses to U.S. military bases and operations around the globe.

The U.S. Armed Forces response isn’t to immediately cut its carbon emissions in order to curb climate change. Rather it is to determine how best to defend against the instability and chaos that climate change may bring to the international community, as well as the threat it poses to U.S. military bases and operations around the globe.

What’s absent is any discussion of the carbon emissions of the U.S. military and plans to change the role that it plays in fueling climate change.

Tamara Lorincz explains:

The U.S. military itself acknowledges that it is the largest institutional consumer of oil.

And the burning of fossil fuels, the burning of petroleum products, oil, is causing the climate crisis. And the U.S. military spends approximately $17 billion on oil, and it needs this oil to fuel its fighter jets, its vehicles, and to power its military bases domestically and internationally. The problem, though, is that the U.S. military emissions and, actually, the military emissions of all countries’ militaries outside their borders are not included in the national greenhouse gas reporting for countries.

A.Woronczuk: Why is that?

Tamara Lorincz: It’s something called international aviation and bunker fuels. This is the fuel that’s used by fighter jets and by warships, for example, outside of state borders. So those military emissions are not included in the national greenhouse gas inventory reporting(*). And the reason why those emissions are not included is because of the lobbying of the United States in the mid-1990s around the Kyoto Protocol. The U.S. delegation at the Kyoto negotiations was able to secure an exemption for military emissions, these international aviation and bunker fuels, and it was also able to secure, under UN Framework Convention on Climate Change guidelines, a confidentiality clause so that it actually doesn’t need to report all of its emissions and it doesn’t have to disaggregate its emissions.

So right now, countries need to abide by the UN Framework Convention guidelines on reporting for greenhouse gases in all different types of sectors, so for transportation, for energy, for buildings, etc. But the military is not a separate category, and the military has these exemptions.

It is required to report its energy use in fuel use domestically, but not internationally. And the United States military is operating all over the world, and all of those greenhouse gas emissions that it’s emitting around the world in its wars overseas, in its thousand bases overseas, those emissions are exempt from its reporting.

A.Woronczuk : And I imagine, then, that if all these are exempt from the national tally, that this must have a significant effect on the figures that are used to make things like emission targets.

Tamara Lorincz : Absolutely. The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the three working group assessment reports that have just been released over the last ten months, none of those three documents refer to military emissions. And the calculations and the analysis that the IPCC is using, it exempts these emissions. So it’s not a full analysis of the emissions and the projections of the IPCC going forward, the kind of reductions that we need for greenhouse gases. They are not including the military emissions.

Tamara Lorincz : Absolutely. The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the three working group assessment reports that have just been released over the last ten months, none of those three documents refer to military emissions. And the calculations and the analysis that the IPCC is using, it exempts these emissions. So it’s not a full analysis of the emissions and the projections of the IPCC going forward, the kind of reductions that we need for greenhouse gases. They are not including the military emissions.

So the forward projections for the IPCC are not adequate, because they’re not including a big bulk of the emissions that are coming right now from the military. It’s not just the U.S. military. It’s–all countries’ militaries have these exemptions. And so the kind of reductions that we need to see for the future are even deeper than what the IPCC is saying. We need to–the military needs to be a sector that the IPCC is considering and is considering as it’s part of its decarbonization pathways. And right now it’s not. And it must be, because we will not be on track to stabilize the climate, to limit the increase in global mean temperatures by two degrees if we don’t include the military. The military emissions, if they continue to be exempt, will keep us off track, and we will not be able to stabilize the climate.

A.Woronczuk: Yeah, and this is an important point to make, because from the climate scientists that we’ve interviewed on The Real News, (TRNN), they’ve all–have basically said that the IPCC reports are conservative in nature; but the point being, do you think that this issue of military emissions being left off of the national tallies, do you think it will be brought up at COP 21 summit in Paris

Tamara Lorincz: For the last ten years there’s evidence that nongovernmental organizations, that civil society organizations, have tried to push the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change Secretariat. They have tried to push the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) scientists to [include] military emissions in the work that they’re doing in the analysis in these 'Conference of the party' negotiations. There has been effort by civil society to get the international community to confront military emissions, but they have not been successful. And we do not expect that at the COP 20 meeting in Peru (2014) or at the COP 21 meeting in Paris, (2015) we do not expect that the UN Framework Convention for Climate Change will put on their official agenda the issue of military emissions. It's going to be up to global civil society to mobilize, to unify together, and to force the Secretariat and to force the IPCC to confront this issue. And State governments must confront this issue. We can no longer allow military emissions to be exempted anymore, because we will never be able to get the stabilization of the climate if we continue with these exemptions.

Tamara Lorincz: For the last ten years there’s evidence that nongovernmental organizations, that civil society organizations, have tried to push the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change Secretariat. They have tried to push the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) scientists to [include] military emissions in the work that they’re doing in the analysis in these 'Conference of the party' negotiations. There has been effort by civil society to get the international community to confront military emissions, but they have not been successful. And we do not expect that at the COP 20 meeting in Peru (2014) or at the COP 21 meeting in Paris, (2015) we do not expect that the UN Framework Convention for Climate Change will put on their official agenda the issue of military emissions. It's going to be up to global civil society to mobilize, to unify together, and to force the Secretariat and to force the IPCC to confront this issue. And State governments must confront this issue. We can no longer allow military emissions to be exempted anymore, because we will never be able to get the stabilization of the climate if we continue with these exemptions.

A Woronczuk: In an imaginary world, let’s say you could advise Chuck Hagel on this matter of the military’s carbon emissions. What policy recommendations would you make to him?

Tamara Lorincz: It was Chuck Hagel as Senator in the mid 1990s that led the Senate campaign to prevent Congress from ratifying the Kyoto Protocol. He was working at the time with the defense community, with the foreign affairs community, to kill the Kyoto Protocol for the U.S., in the U.S. has never ratified it. And, actually, even 16 years ago, Hagel in many speeches and in many documents, denied the veracity of the science of climate change. So he has prevented progress from being made on the climate crisis and he has been the one that has undermined efforts to have collaborate internationally on dealing with the climate crisis. (…)

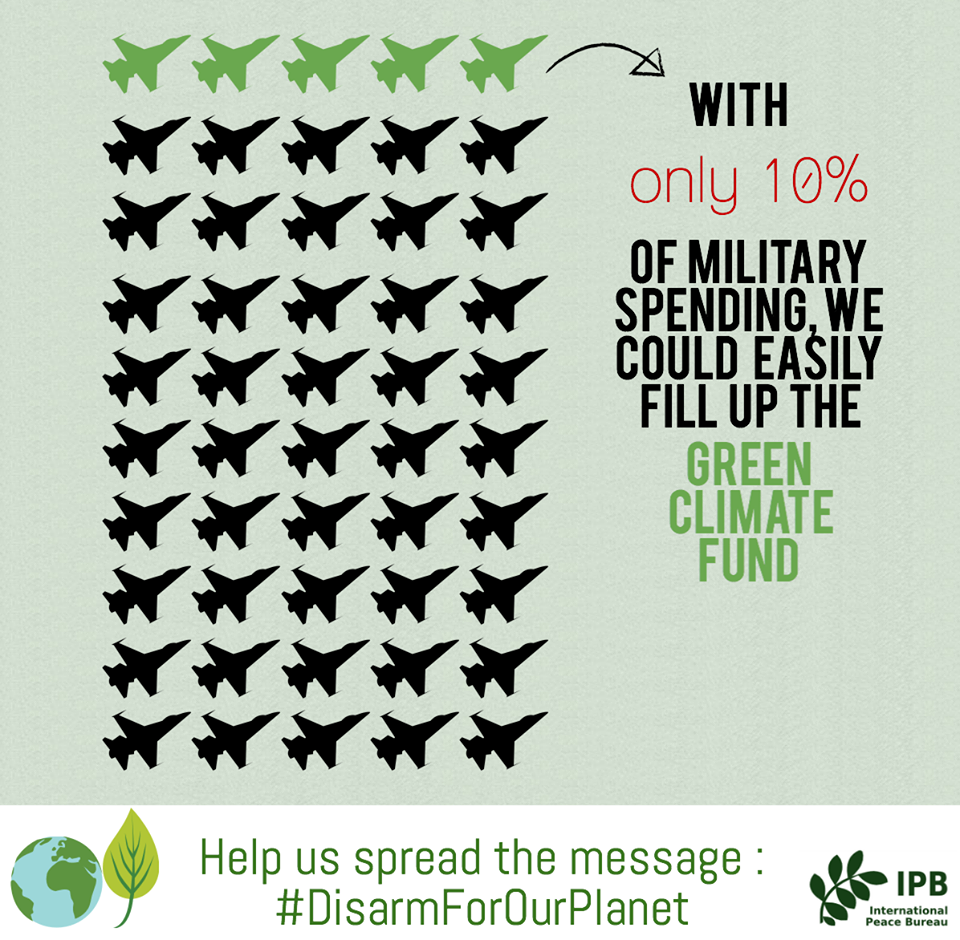

In terms of policy recommendations now, the U.S. government, the international community, has to face the fact that if we are going to be serious about climate change mitigation and adaptation, we must at the same time be serious about peace and disarmament.

We must demilitarize foreign policy, because we will not be able to stay within the carbon budget that has been identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. We simply are not going to be able to maintain a military, this huge military of the United States and all of these wars, and still protect the climate. It’s just not going to be possible. So, the U.S. government and the Secretary of Defense, if they really are concerned about the climate crisis or if they’re concerned about future generations, they’re going to have to get serious about demilitarization.

budget that has been identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. We simply are not going to be able to maintain a military, this huge military of the United States and all of these wars, and still protect the climate. It’s just not going to be possible. So, the U.S. government and the Secretary of Defense, if they really are concerned about the climate crisis or if they’re concerned about future generations, they’re going to have to get serious about demilitarization.

Tamara Lorincz

Senior researcher with the International Peace Bureau, a Rotary International world peace fellow from 2013 to 2014. She serves on the board of the Canadian Voice of Women for Peace. Extracts from interview with The Real News Network (TRNN) producer Anton Woronczuk in Baltimore.

(*) The vast majority, around 75% of DoD’s energy consumption occurs not at facilities but in operations – think hundreds of globetrotting aircraft, ships and vehicles. This very big slice of the military’s energy pie is not subject to DoD’s renewable goals.